This theatrical sculptural expression of grandeur and luxury was expressed in architecture, paintings, the decorative arts and also in music - and became known as the Baroque style. Rulers and artists came from all over Europe to admire the city and its works of art and handmade furniture, then returned to their own countries where they created their own interpretations of the new, anti-Classic style.

Spain, Portugal and Germany were strongly influenced by the Baroque style, but in northern countries, such as the Low Countries and England, the style was quieter and more restrained.

Expansion Of Trade

At the beginning of the 17th century, profitable trading companies were established by the Dutch and also the British, opening up new markets in the Far East and creating colonies. European rulers sought exotic foreign treasures, now antique furniture, to display in their palaces, and the resulting increase in trade led to the establishment of a wealthy and powerful merchant class, which lavished vast sums of money on substantial residences to ensure that they were in keeping with the latest fashions.

Inspired by the influx of exotic materials, craftsmen created flamboyant new designs, mainly for the courts of Europe.

At the beginning of the 17th century, profitable trading companies were established by the Dutch and also the British, opening up new markets in the Far East and creating colonies. European rulers sought exotic foreign treasures, now antique furniture, to display in their palaces, and the resulting increase in trade led to the establishment of a wealthy and powerful merchant class, which lavished vast sums of money on substantial residences to ensure that they were in keeping with the latest fashions.

Inspired by the influx of exotic materials, craftsmen created flamboyant new designs, mainly for the courts of Europe.

The Sovereign State

During the first part of the 17th century - Europe was divided by the bloodshed and by the middle of the century many countries had gained independence from their former rulers.

The treaty of Westphalia in 1648 brought an end to the long war between Spain and the Low Countries and ended the German phase of the Thirty years' War.

The Dutch republic was officially recognized, as was the Swiss Confederation, and around 350 German princes were granted sovereignty. The Holy Roman Emperor was left with diminished power.

This recognition of absolute sovereignty for territories changed the balance of power in Europe. As countries gained independence, rulers and artists worked to forge their own national identities.

During the first part of the 17th century - Europe was divided by the bloodshed and by the middle of the century many countries had gained independence from their former rulers.

The treaty of Westphalia in 1648 brought an end to the long war between Spain and the Low Countries and ended the German phase of the Thirty years' War.

The Dutch republic was officially recognized, as was the Swiss Confederation, and around 350 German princes were granted sovereignty. The Holy Roman Emperor was left with diminished power.

This recognition of absolute sovereignty for territories changed the balance of power in Europe. As countries gained independence, rulers and artists worked to forge their own national identities.

Absolute Power

Louis XIV personified the concept of absolute power - when he became the King of France in 1661, he moved his court to the palace of Versailles and embarked on an ambitious plan to glorify France and his monarchy through art and design.

He ruled as an absolute monarch, and the grandeur of his monarchy inspired other European rulers. Versailles came to symbolize Louis XIV's authority in matters of art - and France became the principal producer of luxury fitted furniture and other objects.

In 1685 Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes, which had granted tolerance to Protestants in France. As a result, many skilled artists and craftsmen fled the country for the protection of the Low Countries - Germany, England and eventually North America.

French trained artisans thus worked for monarchs in other countries, ensuring the dissemination of elaborate French design throughout Europe by the end of the century.

Louis XIV personified the concept of absolute power - when he became the King of France in 1661, he moved his court to the palace of Versailles and embarked on an ambitious plan to glorify France and his monarchy through art and design.

He ruled as an absolute monarch, and the grandeur of his monarchy inspired other European rulers. Versailles came to symbolize Louis XIV's authority in matters of art - and France became the principal producer of luxury fitted furniture and other objects.

In 1685 Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes, which had granted tolerance to Protestants in France. As a result, many skilled artists and craftsmen fled the country for the protection of the Low Countries - Germany, England and eventually North America.

French trained artisans thus worked for monarchs in other countries, ensuring the dissemination of elaborate French design throughout Europe by the end of the century.

Baroque Furniture

Two quite different types of furniture were made during the 17th century - formal furniture, now antique furniture for staterooms and palaces, and simpler pieces intended for domestic use.

Traditionally the aristocracy had moved from one home to another, according to the seasons, but now residences became more permanent. Furniture no longer had to be portable, and substantial pieces were designed for specific rooms. Interiors were very formal and people began to consider rooms as integrated interiors when commissioning furniture. As well as grand salons, wealthy homes had more intimate private rooms that required smaller pieces of furniture.

Two quite different types of furniture were made during the 17th century - formal furniture, now antique furniture for staterooms and palaces, and simpler pieces intended for domestic use.

Traditionally the aristocracy had moved from one home to another, according to the seasons, but now residences became more permanent. Furniture no longer had to be portable, and substantial pieces were designed for specific rooms. Interiors were very formal and people began to consider rooms as integrated interiors when commissioning furniture. As well as grand salons, wealthy homes had more intimate private rooms that required smaller pieces of furniture.

Lavish Style

At the beginning of the century, the Italian Baroque style was dominant in much of Europe. Baroque furniture and fitted furniture was designed on a grand scale and intended to impress.

Pieces were architectural in form, with dramatically carved sculptural elements and lavish decoration, which drew on Classical or Renaissance style motifs.

As the century progressed, trade, especially with the Far East, provided furniture makers with a wealth of exotic new materials - including tortoiseshell, mother of pearl, ebony and rosewood.

Furniture was imported from other countries including lacquerware from the Far East and caned furniture from India - European craftsmen created their own versions.

At the beginning of the century, the Italian Baroque style was dominant in much of Europe. Baroque furniture and fitted furniture was designed on a grand scale and intended to impress.

Pieces were architectural in form, with dramatically carved sculptural elements and lavish decoration, which drew on Classical or Renaissance style motifs.

As the century progressed, trade, especially with the Far East, provided furniture makers with a wealth of exotic new materials - including tortoiseshell, mother of pearl, ebony and rosewood.

Furniture was imported from other countries including lacquerware from the Far East and caned furniture from India - European craftsmen created their own versions.

Key Pieces

Most grand formal rooms had a console, or side table, intended almost purely for display. The finest examples had pietra dura tops and carved and gilded sculptural bases.

Advances in glass making meant that larger mirrors could be made, and it was fashionable to place a matching mirror above each console table in a room. The design elements of the mirrors and tables were repeated in the architectural features of the room, such as door architraves, windows, and fireplace surrounds, creating an integrated sense of design.

Pairs of girandoles or candlestands were placed in front of mirrors so that their light was reflected in them - illuminating rooms that would otherwise have been dark.

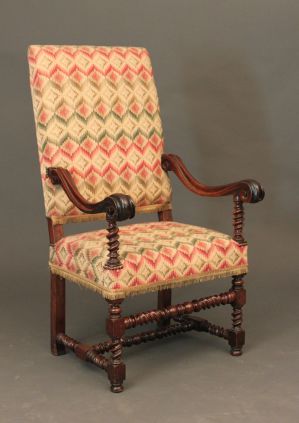

The largest chairs were still reserved for the most important people. Chairs with high backs, sometimes upholstered for greater comfort, were highly desirable.

Wing chairs were first used in France in the middle of the century, a precursor to the bergere. The armchair shape was extended to create the sofa or settee. In 1620 an upholstered settee was commissioned for the great house of Knole, in Kent. This settee had a padded seat and back, held in position by ties on the posts. The design is still known as the Knole settee.

Silks and velvets, usually made in Italy, were phenomenally expensive - only royalty and the wealthiest aristocracy were able to afford upholstered handmade furniture.

Cane, imported from India by Dutch traders became popular as it provided a less expensive method of covering chair backs and seats.

Most grand formal rooms had a console, or side table, intended almost purely for display. The finest examples had pietra dura tops and carved and gilded sculptural bases.

Advances in glass making meant that larger mirrors could be made, and it was fashionable to place a matching mirror above each console table in a room. The design elements of the mirrors and tables were repeated in the architectural features of the room, such as door architraves, windows, and fireplace surrounds, creating an integrated sense of design.

Pairs of girandoles or candlestands were placed in front of mirrors so that their light was reflected in them - illuminating rooms that would otherwise have been dark.

The largest chairs were still reserved for the most important people. Chairs with high backs, sometimes upholstered for greater comfort, were highly desirable.

Wing chairs were first used in France in the middle of the century, a precursor to the bergere. The armchair shape was extended to create the sofa or settee. In 1620 an upholstered settee was commissioned for the great house of Knole, in Kent. This settee had a padded seat and back, held in position by ties on the posts. The design is still known as the Knole settee.

Silks and velvets, usually made in Italy, were phenomenally expensive - only royalty and the wealthiest aristocracy were able to afford upholstered handmade furniture.

Cane, imported from India by Dutch traders became popular as it provided a less expensive method of covering chair backs and seats.

The Age Of the Cabinet

Replacing the carved buffet popular in the previous century, the cabinet - or cabinet on stand - became a real object of desire in households who were wealthy. Cabinets were primarily intended for display purposes, a response to the new passion for collecting among the wealthy, and the need to house all the rare and wonderful objects that they had acquired.

Rather than just a repository for special collections, however, the cabinet itself became a show piece, as skilled craftsmen created large and much more grand scale versions that were works of art in their own right, using precious materials, rare panels of pietra dura, lacquer panels from the Orient, and veneers of ebony and ivory were all incorporated into architecturally inspired cabinets. This was the ultimate expression of wealth!

Replacing the carved buffet popular in the previous century, the cabinet - or cabinet on stand - became a real object of desire in households who were wealthy. Cabinets were primarily intended for display purposes, a response to the new passion for collecting among the wealthy, and the need to house all the rare and wonderful objects that they had acquired.

Rather than just a repository for special collections, however, the cabinet itself became a show piece, as skilled craftsmen created large and much more grand scale versions that were works of art in their own right, using precious materials, rare panels of pietra dura, lacquer panels from the Orient, and veneers of ebony and ivory were all incorporated into architecturally inspired cabinets. This was the ultimate expression of wealth!

Decorative Elements

The wealthiest patrons commissioned handmade furniture, pietra dura tabletops or panels for their cabinets. It was also fashionable to insert exotic and patterned lacquer panels from Japanese or Chinese cabinets into European furniture, now reproduction furniture.

This was, however, prohibitively expensive, so innovative craftsmen developed their own methods of imitating lacquerwork, such as Japanning.

As well as actual lacquered objects, a fashion developed for Oriental scenes - known as Chinoiserie.

Cabinet makers became very skilled at veneering, using exotic hardwoods and inlays. The Low Countries, in particular, produced exquisite floral marquetry.

French boullework created a sumptuous decorative veneer for tables and cabinets using detailed brass and tortoiseshell marquetry.

The wealthiest patrons commissioned handmade furniture, pietra dura tabletops or panels for their cabinets. It was also fashionable to insert exotic and patterned lacquer panels from Japanese or Chinese cabinets into European furniture, now reproduction furniture.

This was, however, prohibitively expensive, so innovative craftsmen developed their own methods of imitating lacquerwork, such as Japanning.

As well as actual lacquered objects, a fashion developed for Oriental scenes - known as Chinoiserie.

Cabinet makers became very skilled at veneering, using exotic hardwoods and inlays. The Low Countries, in particular, produced exquisite floral marquetry.

French boullework created a sumptuous decorative veneer for tables and cabinets using detailed brass and tortoiseshell marquetry.

By the end of the century, French fitted furniture design was highly influential. Louis XIV's palace at Versailles set the style for the fashionable world. Changes in furniture style were keenly watched and interpreted by craftsmen in Britain and the rest of Europe. The finest French pieces - such as tapestries from the Gobelins workshops or cabinets by Boulle - were highly sought after in the grand homes of the very wealthy.

Elements Of Style

The Baroque style used very elaborate decoration and precious materials to create spectacular displays of the owners wealth. Chairs, Tables and Cabinets were embellished with ornate carving, gilding and finely detailed marquetry.

Rich colours, fine tapestries, marble and semi-precious stones, set in scrolling designs, or arabesques, contributed to the sense of status and drama.

Carved Chair

The elaborately pierced splat of this English side chair, non fitted furniture, shows the influence of the engraved designs of Daniel Marot. This piece shows the exquisite wood carving skills demanded of the carvers of the era.

The florid pattern and tall, formal shape are typical of the grandiose Baroque style.

The Baroque style used very elaborate decoration and precious materials to create spectacular displays of the owners wealth. Chairs, Tables and Cabinets were embellished with ornate carving, gilding and finely detailed marquetry.

Rich colours, fine tapestries, marble and semi-precious stones, set in scrolling designs, or arabesques, contributed to the sense of status and drama.

Carved Chair

The elaborately pierced splat of this English side chair, non fitted furniture, shows the influence of the engraved designs of Daniel Marot. This piece shows the exquisite wood carving skills demanded of the carvers of the era.

The florid pattern and tall, formal shape are typical of the grandiose Baroque style.

Gilt Gesso

Originating in Italy, gilt gesso became really fashionable in England and in France. A design would be carved in wood, then coated with layers of gesso - a mixture of glue and powdered chalk.

Once the gesso had hardened, the design was re-carved and gilded. This technique was used to decorate mirrors, tables and chests.

Turned Wood

Created by applying cutting tools to a rotating wooden surface, turned wood was a popular feature of the vernacular handmade furniture of the period, such as the heavy oak baluster of this colonial court cupboard.

Turned wood was also seen on posts, legs, and rungs. As the century progressed, these turnings became less heavy in appearance and more columnar.

Verre Eglomise

This technique imitated the sumptuous effect of gilded glass, and was quite often used to decorate mirrors. The design was actually painted on the underside of the glass, rather than on the front.

The glass was prepared using the base of egg white and water and then gilded. Once dry, the design was engraved into the gilding before the surface was painted.

Marquetry

The practice of arranging small pieces of veneer into an intricate design became a speciality of the century, particularly in the Low Countries, and was very much sought after.

Veneers were made of exotic woods such as mahogany and also native fruitwoods, including plum and cherry. The veneers were used in their natural colours or stained in bright shades.

Silver Furniture

Owning silver furniture epitomized the phenomenal wealth of the privileged few. The exuberant Louis XIV of France ordered suites of solid silver furniture to furnish his palace at Versailles.

Other rulers, such as Charles II of England, imitated this lavish display of wealth withwooden furniture pieces covered with thin sheets of silver.

Pietra Dura

Pietra dura literally means 'Hard Stone'. Pieces of highly polished coloured stones, such as marble or lapis lazuli.

This technique originated in Florence and was mainly used to decorate table tops and also cabinet panels.

The designs could be formal or naturalistic, and commonly featured flowers, birds, animals or landscapes.

Pietra dura literally means 'Hard Stone'. Pieces of highly polished coloured stones, such as marble or lapis lazuli.

This technique originated in Florence and was mainly used to decorate table tops and also cabinet panels.

The designs could be formal or naturalistic, and commonly featured flowers, birds, animals or landscapes.

Drop-Ring Handles

The brass drawer pull is typical of the type found on 17th century fitted and non fitted furniture. Although the level of carving varied from simple circles to florid swags, the basic design of the drop-ring was found on both simple cabinet drawers and ornate pieces that were really designed for the finest residences.

Brass was popular for all furniture detailing at the time.

The brass drawer pull is typical of the type found on 17th century fitted and non fitted furniture. Although the level of carving varied from simple circles to florid swags, the basic design of the drop-ring was found on both simple cabinet drawers and ornate pieces that were really designed for the finest residences.

Brass was popular for all furniture detailing at the time.

Emblem Of Louis XIV

Louis XIV of France (r.1661 - 1715) was renowned from the brilliance and theatricality of his court at Versailles.

Known as the Sun King, his personal emblem was a sun with rays of streaming light, echoing Apollo, the Greek god of light. This motif was used to decorate many pieces of, now antique furniture, and architectural features used at the court.

Louis XIV of France (r.1661 - 1715) was renowned from the brilliance and theatricality of his court at Versailles.

Known as the Sun King, his personal emblem was a sun with rays of streaming light, echoing Apollo, the Greek god of light. This motif was used to decorate many pieces of, now antique furniture, and architectural features used at the court.

Japanning

The process of Japanning used layers of varnish or shellac to imitate the Oriental lacquerwork that was coveted during the 17th century.

True Japanese and Chinese lacquerwork was difficult and expensive to obtain - so Japanning was really developed by European artisans, who used the technique to decorate the wood and metal of cabinets, screens and mirrors in the then fashionable style.

The process of Japanning used layers of varnish or shellac to imitate the Oriental lacquerwork that was coveted during the 17th century.

True Japanese and Chinese lacquerwork was difficult and expensive to obtain - so Japanning was really developed by European artisans, who used the technique to decorate the wood and metal of cabinets, screens and mirrors in the then fashionable style.

Ormolu Mounts

This term, from the French or moulu, meaning 'Ground Gold', describes the technique of gilding with bronze using mercury. Decorative details were cast in bronze then gilded with mercury before being mounted onto handmade furniture.

Ormolu mounts were quite often used to protect the edges of veneered pieces. In cheaper imitations the bronze was cast, finished and then lacquered.

This term, from the French or moulu, meaning 'Ground Gold', describes the technique of gilding with bronze using mercury. Decorative details were cast in bronze then gilded with mercury before being mounted onto handmade furniture.

Ormolu mounts were quite often used to protect the edges of veneered pieces. In cheaper imitations the bronze was cast, finished and then lacquered.

Tapestry

Country houses and palaces across Europe used tapestries for their decoration, using them both to cover walls and to upholster chairs. Woven with wool and silk or linen, they were usually pictorial in design.

Many tapestries originated from the Low Countries, in particular Brussels, Paris and also England. In Paris the Gobelins workshops produced designs for Versailles.

Country houses and palaces across Europe used tapestries for their decoration, using them both to cover walls and to upholster chairs. Woven with wool and silk or linen, they were usually pictorial in design.

Many tapestries originated from the Low Countries, in particular Brussels, Paris and also England. In Paris the Gobelins workshops produced designs for Versailles.

Boullework

This form of marquetry is named after the French cabinet maker Andre' Charles Boulle, who was arguably it's finest exponent.

Boullework combines materials like an intricate jigsaw - using materials such as brass, ebonized wood, ivory and tortoiseshell to create the effect of a painting in marquetry. Brass on a tortoiseshell ground is a popular combination.

This form of marquetry is named after the French cabinet maker Andre' Charles Boulle, who was arguably it's finest exponent.

Boullework combines materials like an intricate jigsaw - using materials such as brass, ebonized wood, ivory and tortoiseshell to create the effect of a painting in marquetry. Brass on a tortoiseshell ground is a popular combination.

Carved Wood

Wood carving became a specialized skill during the 17th century. Elaborate designs decorated chairs, chests and tables. Low relief carving, such as the stylized flower motif was used to decorate hardwoods, such as Oak.

Softer woods allowed carvers to create more detailed patterns, such as those seen on French and Italian furniture.

Wood carving became a specialized skill during the 17th century. Elaborate designs decorated chairs, chests and tables. Low relief carving, such as the stylized flower motif was used to decorate hardwoods, such as Oak.

Softer woods allowed carvers to create more detailed patterns, such as those seen on French and Italian furniture.

Italy

By the early 17th century - Rome was once again the seat of powerful Papacy and entered a period of unprecedented prosperity.

Architects, Artists and Sculptors all really wanted to create a great city that reflected the glory of the Catholic Church, creating new buildings, paintings and monuments on a grand scale.

The aristocracy instigated huge building schemes, creating palazzos that became renowned throughout Europe for their ornate displays of wealth.

The influence of Rome spread throughout the Italian cities - turning the country into the fountainhead of the Baroque movement.

Grand Furniture

The new architectural grandeur demanded extremely impressive furnishings. Formal 17th century Italian furniture, now antique furniture, was sculptural and architectural - it was grand in scale and featured three dimensional carvings of foliage and human figures that were heavily influenced by sculpture.

The makers of opulent palace furniture were quite often sculptors by training rather than cabinet makers, and this had a profound effect on the development of the Baroque style.

In the state apartments and galleries of palazzos, very sumptuous sculptural furniture - such as grand console tables and cabinets, were displayed alongside ancient sculptures, and were regarded in much the same light, as works of art to be looked at rather than used.

The stippone - or great cabinet - was mainly produced in the Grand Ducal Workshops in Florence. Thought to have been derived from the Augsburg cabinet, it was architectural in appearance and in scale and had various small drawers for housing small collections.

Cabinets were embellished with very costly materials, such as gilt bronze and ebony. Around 1667, Leonardo van der Vinne, who was a cabinet maker from the Low Countries, became the director of cabinet makers at the Grand Ducal Workshops and may have introduced floral marquetry techniques.

Stateroom furniture also included console tables with huge marble tops and pietra dura inlays, with heavily carved gilt bases, often with the features of human figures or foliage.

Chairs often had high backs and were frequently upholstered with rich materials, such as velvets and fine silks made in the city of Genoa.

By the early 17th century - Rome was once again the seat of powerful Papacy and entered a period of unprecedented prosperity.

Architects, Artists and Sculptors all really wanted to create a great city that reflected the glory of the Catholic Church, creating new buildings, paintings and monuments on a grand scale.

The aristocracy instigated huge building schemes, creating palazzos that became renowned throughout Europe for their ornate displays of wealth.

The influence of Rome spread throughout the Italian cities - turning the country into the fountainhead of the Baroque movement.

Grand Furniture

The new architectural grandeur demanded extremely impressive furnishings. Formal 17th century Italian furniture, now antique furniture, was sculptural and architectural - it was grand in scale and featured three dimensional carvings of foliage and human figures that were heavily influenced by sculpture.

The makers of opulent palace furniture were quite often sculptors by training rather than cabinet makers, and this had a profound effect on the development of the Baroque style.

In the state apartments and galleries of palazzos, very sumptuous sculptural furniture - such as grand console tables and cabinets, were displayed alongside ancient sculptures, and were regarded in much the same light, as works of art to be looked at rather than used.

The stippone - or great cabinet - was mainly produced in the Grand Ducal Workshops in Florence. Thought to have been derived from the Augsburg cabinet, it was architectural in appearance and in scale and had various small drawers for housing small collections.

Cabinets were embellished with very costly materials, such as gilt bronze and ebony. Around 1667, Leonardo van der Vinne, who was a cabinet maker from the Low Countries, became the director of cabinet makers at the Grand Ducal Workshops and may have introduced floral marquetry techniques.

Stateroom furniture also included console tables with huge marble tops and pietra dura inlays, with heavily carved gilt bases, often with the features of human figures or foliage.

Chairs often had high backs and were frequently upholstered with rich materials, such as velvets and fine silks made in the city of Genoa.

The Age Of Learning

With all the new buildings and the interest in humanist learning, many wealthy patrons now had important libraries, this required a new form of fitted furniture - built in bookcases.

Influenced again by architecture, these bookcases often had pilasters or columns - and sometimes features statues of carved urns on the cornice.

Grand Beds

Late 17th century Italian beds were really an expression of the upholsterers art, making use of the fine textiles that were locally produced - usually no wood at all was visible.

A tester who was often draped in silk or damask, would be supported from above the head, and upholstered panels surrounded the mattress. This type of bed remained very popular until the end of the 18th century so it is difficult to date them with any certainty.

Eastern Influences

The Venetians were producing lacquered furniture - a skill that local craftsmen learned through the cities trading links with the East.

Green and gold lacquer became a speciality of Venice until the 18th century. Good quality wood was not available locally, which would explain the popularity of techniques such as lacquering, which covers the surface of the wood completely, allowing the craftsmen to make the most out of the materials they had available to them at the time.

Vernacular Styles

In Italy there was a tremendous difference between the furniture made for daily use in the ordinary rooms of a palazzo or villa and that on display in the state apartments.

Utilitarian handmade furniture, such as x-framed chairs, stools, cassone (chests) and tables were made by carpenters or joiners - using local fruitwood or walnut.

With all the new buildings and the interest in humanist learning, many wealthy patrons now had important libraries, this required a new form of fitted furniture - built in bookcases.

Influenced again by architecture, these bookcases often had pilasters or columns - and sometimes features statues of carved urns on the cornice.

Grand Beds

Late 17th century Italian beds were really an expression of the upholsterers art, making use of the fine textiles that were locally produced - usually no wood at all was visible.

A tester who was often draped in silk or damask, would be supported from above the head, and upholstered panels surrounded the mattress. This type of bed remained very popular until the end of the 18th century so it is difficult to date them with any certainty.

Eastern Influences

The Venetians were producing lacquered furniture - a skill that local craftsmen learned through the cities trading links with the East.

Green and gold lacquer became a speciality of Venice until the 18th century. Good quality wood was not available locally, which would explain the popularity of techniques such as lacquering, which covers the surface of the wood completely, allowing the craftsmen to make the most out of the materials they had available to them at the time.

Vernacular Styles

In Italy there was a tremendous difference between the furniture made for daily use in the ordinary rooms of a palazzo or villa and that on display in the state apartments.

Utilitarian handmade furniture, such as x-framed chairs, stools, cassone (chests) and tables were made by carpenters or joiners - using local fruitwood or walnut.

Gilded Frame

This gilded, carved picture frame depicts the legend of Paris. The maker was Filippo Parodi, who was perhaps the best known Genoese carver of the late 17th century, and he worked in Bernini's studio.

As well as the sculptural style figures, the frame also includes foliage and shell motifs, which were very popular throughout the 17th century. The portrait is by Pierre Mignard and shows Maria Mancini.

This gilded, carved picture frame depicts the legend of Paris. The maker was Filippo Parodi, who was perhaps the best known Genoese carver of the late 17th century, and he worked in Bernini's studio.

As well as the sculptural style figures, the frame also includes foliage and shell motifs, which were very popular throughout the 17th century. The portrait is by Pierre Mignard and shows Maria Mancini.

Walnut Armorial Cassone

The raised lid is carved with a design of beads, leaves and a fish scale type pattern, while the front and ends of the cassone (chest) retain mannerist features typical of the Renaissance period - strapwork decoration and segmented panels.

The cassone stands on paw feet and bears the coat of arms of the Guicciardini family from Florence. These chests were quite often given as wedding presents.

The raised lid is carved with a design of beads, leaves and a fish scale type pattern, while the front and ends of the cassone (chest) retain mannerist features typical of the Renaissance period - strapwork decoration and segmented panels.

The cassone stands on paw feet and bears the coat of arms of the Guicciardini family from Florence. These chests were quite often given as wedding presents.

Andrea Brustolon

Renowned for fantastic carved furniture, Andrea Brusolon (1662-1732) was a pupil of the Genoese sculptor Filippo Parodi.

Originally trained as a stone carver, Brustolon took up wood carving and created many different types of fitted and non fitted furniture, ranging from frames, to stands and to tables. He is best known really for his extravagantly carved chairs, which were designed more as works of art than as comfortable seating.

Few pieces have survived today, but several of his drawings have. It is likely that Brustolon travelled to Rome during his apprenticeship. In keeping with the Roman style of the time, Brustolon's furniture is naturalistic and quite often allegorical, with figural supports, exuberant foliage and animals.

Parodi's influence is very evident.

Renowned for fantastic carved furniture, Andrea Brusolon (1662-1732) was a pupil of the Genoese sculptor Filippo Parodi.

Originally trained as a stone carver, Brustolon took up wood carving and created many different types of fitted and non fitted furniture, ranging from frames, to stands and to tables. He is best known really for his extravagantly carved chairs, which were designed more as works of art than as comfortable seating.

Few pieces have survived today, but several of his drawings have. It is likely that Brustolon travelled to Rome during his apprenticeship. In keeping with the Roman style of the time, Brustolon's furniture is naturalistic and quite often allegorical, with figural supports, exuberant foliage and animals.

Parodi's influence is very evident.

Florentine Console Table

This table would have been made of carved and gilded wood, the top is supported by kneeling mythological figures known as harpies.

The figures are muscular, in keeping with the bold, masculine Baroque style. The theme is borrowed from contemporary Roman designs - although these harpies are more restrained than examples from Rome.

This table would have been made of carved and gilded wood, the top is supported by kneeling mythological figures known as harpies.

The figures are muscular, in keeping with the bold, masculine Baroque style. The theme is borrowed from contemporary Roman designs - although these harpies are more restrained than examples from Rome.

Florentine Cabinet

This cabinet, produced in the Grand Ducal workshops in Florence, is decorated with pietra dura panels depicting mythological scenes.

The architectural influence on Italian Baroque handmade furniture design can be seen in the use of pilasters, arched panels, and pediments - in the structural form of the piece. Mythology was an extremely common theme for decoration, and the meanings would have been widely understood.

This cabinet, produced in the Grand Ducal workshops in Florence, is decorated with pietra dura panels depicting mythological scenes.

The architectural influence on Italian Baroque handmade furniture design can be seen in the use of pilasters, arched panels, and pediments - in the structural form of the piece. Mythology was an extremely common theme for decoration, and the meanings would have been widely understood.

Walnut Table

The octagonal table top rests on triform supports, which terminate in male terms (stylized human figures) carved with scrolling foliage - on paw feet.

The top of the supports have a square panel centred by a wine glass and an illegible inscription.

Lion Commode

The commode is made of walnut with exquisite inlays of ivory and mother of pearl, this depicts images of vanity, justice and other allegorical figures, surrounded by putti, flowers, leaves, cartouches and volutes.

The sides are sloped and decorated with inlay and gilding. The front of the commode is bow shaped and has three drawers and iron fittings.

The octagonal table top rests on triform supports, which terminate in male terms (stylized human figures) carved with scrolling foliage - on paw feet.

The top of the supports have a square panel centred by a wine glass and an illegible inscription.

Lion Commode

The commode is made of walnut with exquisite inlays of ivory and mother of pearl, this depicts images of vanity, justice and other allegorical figures, surrounded by putti, flowers, leaves, cartouches and volutes.

The sides are sloped and decorated with inlay and gilding. The front of the commode is bow shaped and has three drawers and iron fittings.

Pietra Dura & Scagliola

Florentine handmade furniture - table tops and cabinet panels inlaid with richly coloured, semi-precious stones were highly coveted by wealthy patrons during the 17th century.

Pietra Dura (hard stone) involves making a mosaic of hard or semi-precious stones. The manufacture of Pietra Dura was just one of the trades that supplied furniture makers from the Renaissance. Scagliola created a similar effect at much less of a cost.

Originating in Italy, the full name - Commesso di pietra dura - describes stones that are fitted together so closely that the joins are invisible. The mosaic is glued to a slate base for stability. The elaborate process of creating pictures from stone has remained the same for centuries.

Pietra dura was used for table tops and provided a good contrast with the gilt console bases that were typical of the time. The rich colours and floral or naturalistic pictures not only displayed the expensive materials - the dedicated craftsmanship required to complete such work was admired and coveted by royal and aristocratic patrons.

Teamwork

The very finest workshops produced pietra dura in teams. An artist or sculptor would prepare the design, then other craftsmen chose the stones and after polishing them would cut them into fine slices.

Tracings of the design were used to cut the stones into the right shapes and these were then, very carefully, glued and pieced together in position on a base. If the design was particularly delicate, it would be lined with slate. Finally the stones would be polished with abrasive powders.

The Grand Ducal Workshops

These Florentine workshops, situated in the galleries of the Uffizi Palace, were pre-eminent in developing pietra dura furnishings. Other workshops sometimes poached Florentine artisans so that they could teach their skills elsewhere.

In 1588, Ferdinand I de'Medici made them the Court workshop, making fitted and nonfitted furniture as well as mosaics.

The works were commissioned for the Grand Duke's residences as well as for important European families. Products ranged from cabinets and table tops to boxes and architectural features.

Henry IV and Louis XIII of France established their own royal workshops under the Louvre Palace in Paris.

Florentine Cabinet

This wooden cabinet, now antique furniture, produced at the Grand Ducal Workshops in Florence, has pietra dura panels depicting mythological scenes. The architectural influence on Italian Baroque handmade furniture design can be seen in the structural form of the piece.

This wooden cabinet, now antique furniture, produced at the Grand Ducal Workshops in Florence, has pietra dura panels depicting mythological scenes. The architectural influence on Italian Baroque handmade furniture design can be seen in the structural form of the piece.

Scagliola

Scagliola is false marble. The first documented examples of it appeared at the end of the 17th century in Germany and in Italy.

Pietra dura panels and table tops, for fitted and non fitted furniture, especially those from the Grand Ducal Workshops in Florence, were prohibitively expensive, so much less wealthy patrons were very keen to find an alternative and commissioned craftsmen to create an imitation - Scagliola.

Scagliola is false marble. The first documented examples of it appeared at the end of the 17th century in Germany and in Italy.

Pietra dura panels and table tops, for fitted and non fitted furniture, especially those from the Grand Ducal Workshops in Florence, were prohibitively expensive, so much less wealthy patrons were very keen to find an alternative and commissioned craftsmen to create an imitation - Scagliola.

The Technique

Scagliola is produced by grinding the mineral selenite into a powder and mixing it with coloured pigments and animal glue to produce a plaster like substance. As with pietra dura, a drawing is transferred to a stone slab upon which it is engraved.

Unlike marquetry or pietra dura, which are both inlaid, the liquid scagliola is poured into the engraved hollows in the stone, then left to set.

Additional effects, such as veining or different colour variations, are achieved by adding chips of marble, granite, alabaster, porphyry or other stones to the mixture, or by engraving and filling the hardened plaster a second time. Once the plaster has finally hardened, it is polished with linseed oil to create the desired finish.

Scagliola is produced by grinding the mineral selenite into a powder and mixing it with coloured pigments and animal glue to produce a plaster like substance. As with pietra dura, a drawing is transferred to a stone slab upon which it is engraved.

Unlike marquetry or pietra dura, which are both inlaid, the liquid scagliola is poured into the engraved hollows in the stone, then left to set.

Additional effects, such as veining or different colour variations, are achieved by adding chips of marble, granite, alabaster, porphyry or other stones to the mixture, or by engraving and filling the hardened plaster a second time. Once the plaster has finally hardened, it is polished with linseed oil to create the desired finish.

Low Countries

During the first half of the 17th century, the northern provinces became a major maritime power. The city of Amsterdam grew prosperous, and the influx of exotic goods and materials brought from the Far East by the Dutch East India Company made this city a real haven for artists and craftsmen.

Traditional manufacturers flourished in the southern Netherlands, which at the time was still under Spanish Hapsburg rule. Flemish craftsmen were known in particular for their luxurious tapestries, stamped or gilt leather and weavings, used for both upholstery and wall hangings.

Popular Styles

Early 17th century furniture, now antique furniture, from the Low Countries was generally quite simple, although more elaborate pieces were made for wealthy patrons. For much of the century, the four-door court cupboard was the most important piece of furniture in wealthy homes. Usually made of Oak and often decorated with intricately carved figures, or intarsia panels depicting architectural scenes.

Walnut then became the timber of choice after 1660 and was quite often embellished with inlays or exotic veneered panels. In Holland, the 'arched' cupboard with two long panelled doors remained fashionable.

Luxurious Cabinets

As in Italy, the Augsburg cabinet was influential. Early in the century, Flemish craftsmen in Antwerp made small table cabinets veneered with imported ebony, they also begun to use new and exotic imports as veneers - perhaps influenced by the Northern Provinces' trade with the East.

Table cabinets then gave way to 'cabinets on stands', decorated with ebony, mother of pearl and tortoiseshell veneers. Cabinets later had carved stands with legs made from gilded caryatids or ebonized wood - this can be seen today with reproduction furniture.

Later in the century, craftsmen such as Jan van MeKeren, a cabinet maker in Amsterdam, decorated large cabinets on stands and tables with intricate floral marquetry, inspired by the still life floral paintings that were popular at the time.

The contrasting colours of ebony from Madagascar, purple amaranth from Guyana, rosewood from Brazil and sandalwood from India were combined to create marquetry of consummate skill. Exported to France and then England - these cabinets provided inspiration for cabinet makers there, who developed their own styles of veneering.

Everyday Pieces

Floral marquetry was not just used to embellish cabinets - side tables were often decorated in the same way. More typical of the Low Countries, however, were tables and cupboards decorated with a wealth of naturalistic carving.

Chests of drawers were often made of oak, polished or stained to resemble ebony. Ebony or stained pearwood was used for mouldings.

Chairs tended to be rectangular with low or high backs. Usually made of walnut and upholstered in leather, cloth or velvet with brass studs.

As the century advanced, inspired by imports from India, chair seats and backs were made of cane.

The legs were linked by stretchers. The artist Crispin van den Passe's Boutique Menuiserie, published in Amsterdam in 1642, showed elements of Mannerism in chair design, but it also included simpler chairs with straight backs, double stretchers, and carved arms terminating in dolphins.

French Influence

Towards the end of the century, the dazzling furniture of the Court at Versailles became a new source of inspiration, compounded by an influx of Huguenot designers and craftsmen, such as Daniel Marot (featured in the next article) fleeing religious persecution in France.

The French influence soon became evident as Dutch furniture and fitted furniture, became more sculptural and less rectangular. Based on Marot's designs, chairs now had tall, richly carved backs with crested back rails.

During the first half of the 17th century, the northern provinces became a major maritime power. The city of Amsterdam grew prosperous, and the influx of exotic goods and materials brought from the Far East by the Dutch East India Company made this city a real haven for artists and craftsmen.

Traditional manufacturers flourished in the southern Netherlands, which at the time was still under Spanish Hapsburg rule. Flemish craftsmen were known in particular for their luxurious tapestries, stamped or gilt leather and weavings, used for both upholstery and wall hangings.

Popular Styles

Early 17th century furniture, now antique furniture, from the Low Countries was generally quite simple, although more elaborate pieces were made for wealthy patrons. For much of the century, the four-door court cupboard was the most important piece of furniture in wealthy homes. Usually made of Oak and often decorated with intricately carved figures, or intarsia panels depicting architectural scenes.

Walnut then became the timber of choice after 1660 and was quite often embellished with inlays or exotic veneered panels. In Holland, the 'arched' cupboard with two long panelled doors remained fashionable.

Luxurious Cabinets

As in Italy, the Augsburg cabinet was influential. Early in the century, Flemish craftsmen in Antwerp made small table cabinets veneered with imported ebony, they also begun to use new and exotic imports as veneers - perhaps influenced by the Northern Provinces' trade with the East.

Table cabinets then gave way to 'cabinets on stands', decorated with ebony, mother of pearl and tortoiseshell veneers. Cabinets later had carved stands with legs made from gilded caryatids or ebonized wood - this can be seen today with reproduction furniture.

Later in the century, craftsmen such as Jan van MeKeren, a cabinet maker in Amsterdam, decorated large cabinets on stands and tables with intricate floral marquetry, inspired by the still life floral paintings that were popular at the time.

The contrasting colours of ebony from Madagascar, purple amaranth from Guyana, rosewood from Brazil and sandalwood from India were combined to create marquetry of consummate skill. Exported to France and then England - these cabinets provided inspiration for cabinet makers there, who developed their own styles of veneering.

Everyday Pieces

Floral marquetry was not just used to embellish cabinets - side tables were often decorated in the same way. More typical of the Low Countries, however, were tables and cupboards decorated with a wealth of naturalistic carving.

Chests of drawers were often made of oak, polished or stained to resemble ebony. Ebony or stained pearwood was used for mouldings.

Chairs tended to be rectangular with low or high backs. Usually made of walnut and upholstered in leather, cloth or velvet with brass studs.

As the century advanced, inspired by imports from India, chair seats and backs were made of cane.

The legs were linked by stretchers. The artist Crispin van den Passe's Boutique Menuiserie, published in Amsterdam in 1642, showed elements of Mannerism in chair design, but it also included simpler chairs with straight backs, double stretchers, and carved arms terminating in dolphins.

French Influence

Towards the end of the century, the dazzling furniture of the Court at Versailles became a new source of inspiration, compounded by an influx of Huguenot designers and craftsmen, such as Daniel Marot (featured in the next article) fleeing religious persecution in France.

The French influence soon became evident as Dutch furniture and fitted furniture, became more sculptural and less rectangular. Based on Marot's designs, chairs now had tall, richly carved backs with crested back rails.

Cabinet-On-Stand

The cabinet is usually made of oak, and then veneered with a variety of woods, for example walnut, palm and purple wood, with lacquer and ray-skin panels forming part of the inlay.

The cabinet stands on six turned, squared baluster legs joined by flat stretchers. A wealthy status symbol for its time, this cabinet is the earliest known example of Dutch furniture made using lacquer panels and polished ray-skin cut from an earlier Japanese coffer.

The original piece was probably Imported from the Netherlands by the Dutch East India Company, but was probably no longer fashionable.

The desirable exotic materials from the East would then have been removed and used to decorate a new, more fashionable, piece of antique furniture.

The cabinet is usually made of oak, and then veneered with a variety of woods, for example walnut, palm and purple wood, with lacquer and ray-skin panels forming part of the inlay.

The cabinet stands on six turned, squared baluster legs joined by flat stretchers. A wealthy status symbol for its time, this cabinet is the earliest known example of Dutch furniture made using lacquer panels and polished ray-skin cut from an earlier Japanese coffer.

The original piece was probably Imported from the Netherlands by the Dutch East India Company, but was probably no longer fashionable.

The desirable exotic materials from the East would then have been removed and used to decorate a new, more fashionable, piece of antique furniture.

Giltwood Pier Table & Mirror

This is one of a pair of tables , each with a matching large mirror above. This heavily carved gilt table has a serpentine marble top and scrolled serpentine-panelled legs joined by a cross stretcher.

In the centre is a carved urn. The coat of arms of the original owner is carved into the top of the mirror frame. (Note: Table picture unavailable)

Doll's House

This doll's house was commissioned by Petronella Oortman, a very wealthy woman from Amsterdam. She ordered porcelain objects from China and had the city's handmade furniture makers and artists decorate the interior.

Costing as much as a townhouse along the canal, this was not a toy for children.

Its importance for the historian is in the design and placement of the furniture.

Dutch Oak & Marquetry Table

This table is typical of Low Countries' design, with square baluster legs and flat stretchers. Designed to stand against a wall, fitted furniture, only the visible surfaces are decorated with marquetry.

The end of the Thirty Years War in 1648 marked the beginning of German federalism. From this time, Germany was made up of small sovereign states that were ruled by wealthy princes.

The most powerful nation in the Baltic area was Sweden By 1660, under Charles XI, it had reached the height of its power.

Influences

Styles of furniture varied from one part of Germany to another, this was because each principality had its own court. The Bavarian Electors built the Residenz in Munich with a style and a luxury that made King Gustav Adolf of Sweden jealous.

Following an exile in Brussels, Elector Max II Emanuel (1680-1724) returned to Bavaria with very expensive Antwerp handmade furniture. During his second exile, in France, he became familiar with the French Baroque and sent Bavarian craftsmen to France to study, who bought the style back home.

In Germany, by the beginning of the 18th century, the heavy opulent Baroque style was making way for the curvaceous Rococo forms that reached their creative high point in church and castle interiors. Partly due to the guild system, the German cities were a little behind in development, generally taking the lead from the masterpieces.

Princely Cabinets

In 1631, the city of Augsburg sent an ebony cabinet decorated with precious materials to the King of Sweden as a piece offering. Augsburg was the stronghold of, now antique furniture design, and such a large number of intarsia cabinets were imported to Spain that in1603 King Philip III introduced a ban on the importation of Augsburg goods.

Curiosity cabinets, embellished with very fine inlays of ivory, silver, amber and precious stones, or with coloured engravings and porcelain plaques were sought by noblemen and emulated throughout Europe. Augsburg also produced opulent embossed and engraved silver fitted and non fitted furniture for the export markets.

Travel Cabinet

This ebony cabinet from Southern Germany is decorated with ivory inlay. The small front opens to reveal many small drawers flanking a second section with a lockable door.

All of the surfaces are decorated with ivory foliate inlay, and the case stands on flat ball feet.

The most powerful nation in the Baltic area was Sweden By 1660, under Charles XI, it had reached the height of its power.

Influences

Styles of furniture varied from one part of Germany to another, this was because each principality had its own court. The Bavarian Electors built the Residenz in Munich with a style and a luxury that made King Gustav Adolf of Sweden jealous.

Following an exile in Brussels, Elector Max II Emanuel (1680-1724) returned to Bavaria with very expensive Antwerp handmade furniture. During his second exile, in France, he became familiar with the French Baroque and sent Bavarian craftsmen to France to study, who bought the style back home.

In Germany, by the beginning of the 18th century, the heavy opulent Baroque style was making way for the curvaceous Rococo forms that reached their creative high point in church and castle interiors. Partly due to the guild system, the German cities were a little behind in development, generally taking the lead from the masterpieces.

Princely Cabinets

In 1631, the city of Augsburg sent an ebony cabinet decorated with precious materials to the King of Sweden as a piece offering. Augsburg was the stronghold of, now antique furniture design, and such a large number of intarsia cabinets were imported to Spain that in1603 King Philip III introduced a ban on the importation of Augsburg goods.

Curiosity cabinets, embellished with very fine inlays of ivory, silver, amber and precious stones, or with coloured engravings and porcelain plaques were sought by noblemen and emulated throughout Europe. Augsburg also produced opulent embossed and engraved silver fitted and non fitted furniture for the export markets.

Travel Cabinet

This ebony cabinet from Southern Germany is decorated with ivory inlay. The small front opens to reveal many small drawers flanking a second section with a lockable door.

All of the surfaces are decorated with ivory foliate inlay, and the case stands on flat ball feet.

Swedish Gilded Mirror Frame

This gilt bronze frame, attributed to Burchard Precht. The bevelled rectangular plate with arched cresting within a conforming slip-mounted frame cast with egg-and-dart and pendant flowers, shells and rocaille, the scalloped crest surmounted by a mask flanked by frolicking putti beneath central flower basket, cresting plates replaced, the left putto to top replaced in carved wood, regilt.

Vernacular Styles

In Germany and Scandinavia huge, architectural wardrobes with very heavy cornices, known as schranke, remained popular in wealthy middle-class houses throughout the century. These had two doors over two drawers.

In the north they were usually made of oak and very quite often heavily carved - in the south they were more likely to be made from local fruitwood or walnut. The chest was an important household item of handmade furniture well into the 18th century.

Upholstered armchairs with carved top rails were made for the heads of households. These had turned arms and curled, almost scrolled feet.

In Sweden and Germany suites of stools, armchairs and chairs were upholstered in leather, or occasionally they were upholstered in imported silk. In less grand homes it was very common to find stools and benches set around long, plank tables.

Decorative Effects

German craftsmen were renowned for their use of walnut veneer, and later for ebony. Eger in Bonemia was well known for cabinets using sculptural relief or intarsia panels. Nowantique furniture, decorated with Boullework became quite popular in southern Germany at the end of the century. Augsburg craftsmen mastered the technique, and produced fine examples of the style.

Berlin became renowned for japanned furniture, especially for the tables, cabinets, gueridons, and musical instrument cases with japanned decorations on a white ground designed by Gerhard Dagly.

In Paris his non fitted furniture pieces were described as 'Berlin' cabinets. Cabinets decorated with red and blue lacquer from Dresden and Brandenburg were also highly coveted abroad.

The Baroque Schloss Biebrich (palace), south of Wiesbaden

This three winged palace on the banks of the Rhine is a great example of the Baroque style, with its bold colour scheme and carved statues looking down from the roof.

In Germany and Scandinavia huge, architectural wardrobes with very heavy cornices, known as schranke, remained popular in wealthy middle-class houses throughout the century. These had two doors over two drawers.

In the north they were usually made of oak and very quite often heavily carved - in the south they were more likely to be made from local fruitwood or walnut. The chest was an important household item of handmade furniture well into the 18th century.

Upholstered armchairs with carved top rails were made for the heads of households. These had turned arms and curled, almost scrolled feet.

In Sweden and Germany suites of stools, armchairs and chairs were upholstered in leather, or occasionally they were upholstered in imported silk. In less grand homes it was very common to find stools and benches set around long, plank tables.

Decorative Effects

German craftsmen were renowned for their use of walnut veneer, and later for ebony. Eger in Bonemia was well known for cabinets using sculptural relief or intarsia panels. Nowantique furniture, decorated with Boullework became quite popular in southern Germany at the end of the century. Augsburg craftsmen mastered the technique, and produced fine examples of the style.

Berlin became renowned for japanned furniture, especially for the tables, cabinets, gueridons, and musical instrument cases with japanned decorations on a white ground designed by Gerhard Dagly.

In Paris his non fitted furniture pieces were described as 'Berlin' cabinets. Cabinets decorated with red and blue lacquer from Dresden and Brandenburg were also highly coveted abroad.

The Baroque Schloss Biebrich (palace), south of Wiesbaden

This three winged palace on the banks of the Rhine is a great example of the Baroque style, with its bold colour scheme and carved statues looking down from the roof.

Armoire

17th century armoire, a Fassadebschrank - intarsia on oak with a pine base.

England

During the reign of James I, most handmade furniture was made of oak and was limited to joint stools, chairs with plain or spiral turned legs, chests, and long trestle tables. Decoration was confined to elaborate carving on chairs, chests, and settees.

The aristocracy of Wales and Scotland tended to follow the lead of the dominant English court style.

Foreign Influences

During the reign of Charles I, craftsmen from France, Italy, and the Low Countries came to work on state apartments and grand houses. Influenced by designs from the Low Countries, English furniture, now reproduction furniture, was more restrained than Italian Baroque pieces.

Upholstered furniture was made for grand houses and apartments. Chairs generally had quite low, square backs, upholstered with tapestry or leather, and armchairs had seat cushions and padded arms covered with upholstery. Settees were often made as part of a suit with matching chairs.

The Restoration

Furniture, and fitted furniture, was commonly made of plain woods such as oak, ash, elm or beach under Oliver Cromwell, whose government did not condone lavish displays of ornament, but the situation did change after the restoration of the monarchy in 1660.

Charles II had spent his exile in Europe and bought back the latest fashions to England. Court life under Charles II was far less formal, creating a demand for small folding tables, card tables, and gateleg dining tables. Walnut became the most popular wood, and techniques such as veneering and caning were fashionable. Caned furniture with twist-turned frames was considered quintessentially English.

High-Backed Side Chairs

Made from imported walnut, these chairs, with there carved and pierced back splat, is similar to engravings published by Marot. They have cabriole legs terminating in 'horse-bone' feet, but has stretchers.

During the reign of James I, most handmade furniture was made of oak and was limited to joint stools, chairs with plain or spiral turned legs, chests, and long trestle tables. Decoration was confined to elaborate carving on chairs, chests, and settees.

The aristocracy of Wales and Scotland tended to follow the lead of the dominant English court style.

Foreign Influences

During the reign of Charles I, craftsmen from France, Italy, and the Low Countries came to work on state apartments and grand houses. Influenced by designs from the Low Countries, English furniture, now reproduction furniture, was more restrained than Italian Baroque pieces.

Upholstered furniture was made for grand houses and apartments. Chairs generally had quite low, square backs, upholstered with tapestry or leather, and armchairs had seat cushions and padded arms covered with upholstery. Settees were often made as part of a suit with matching chairs.

The Restoration

Furniture, and fitted furniture, was commonly made of plain woods such as oak, ash, elm or beach under Oliver Cromwell, whose government did not condone lavish displays of ornament, but the situation did change after the restoration of the monarchy in 1660.

Charles II had spent his exile in Europe and bought back the latest fashions to England. Court life under Charles II was far less formal, creating a demand for small folding tables, card tables, and gateleg dining tables. Walnut became the most popular wood, and techniques such as veneering and caning were fashionable. Caned furniture with twist-turned frames was considered quintessentially English.

High-Backed Side Chairs

Made from imported walnut, these chairs, with there carved and pierced back splat, is similar to engravings published by Marot. They have cabriole legs terminating in 'horse-bone' feet, but has stretchers.

Hall Chair

This chair is based on the Italian sgabello design, The oak is carved and painted, with a shell-shaped back and pendant mask with swags on the front. c.1635

Rebuilding London

A huge building boom after the great fire of London in 1666 led to specialization within the woodworking trades. Cabinet makers made case handmade furniture, stands and tables, while joiners - and the gilders and wood carvers who worked with them - concentrated on architectural features, bedsteads and mirror frames. Chair-making also became a specialist craft.

Trade between the Low Countries and England increased after the accession of William III and Mary in 1689.

The European influence on furniture was compounded by the arrival in England of French Huguenot craftsmen, some of whom became cabinet makers to the royal household.

Skilled Craftsmanship

Cabinets were now often veneered with walnut, maple, yew, holly olive, beech, and also fruitwoods. Burr woods were especially desirable. Some woods were cut across the grain to create an 'oyster' veneer.

The most elaborate forms of veneering used floral, seaweed, or arabesque marquetry.

Other cabinets were japanned, to imitate lacquer, or were covered in patterned gesso to create a raised and gilded appearance. Now reproduction furniture, Chests on stands were replaced by bureau cabinets, often topped with pediments or domes intended for the display of expensive porcelain. Clothes presses and livery cupboards were commonplace, as were chests of drawers and kneehole desks.

Tables ranged from oak trestles to grand console tables. These were often designed to stand beneath large, ornate mirrors. High-backed chairs with caned seats and backs were popular, as were chairs in the style of Daniel Marot, which had long carved or pierced back splats.

As the century drew to a close, fine furniture, including fitted furniture, was no longer made solely for grand palaces. Simpler, well crafted pieces were also being made for wealthy city merchants and the landed gentry, paving the way for the elegant styles prevalent in the 18th century.

Japanese Lacquer Cabinet On English Stand

Designed to stand against the wall, this cabinet is only decorated on the front. Such fine lacquered pieces would have been great status symbols. The imported Japanese cabinets rests on an English giltwood stand.

A huge building boom after the great fire of London in 1666 led to specialization within the woodworking trades. Cabinet makers made case handmade furniture, stands and tables, while joiners - and the gilders and wood carvers who worked with them - concentrated on architectural features, bedsteads and mirror frames. Chair-making also became a specialist craft.

Trade between the Low Countries and England increased after the accession of William III and Mary in 1689.

The European influence on furniture was compounded by the arrival in England of French Huguenot craftsmen, some of whom became cabinet makers to the royal household.

Skilled Craftsmanship

Cabinets were now often veneered with walnut, maple, yew, holly olive, beech, and also fruitwoods. Burr woods were especially desirable. Some woods were cut across the grain to create an 'oyster' veneer.

The most elaborate forms of veneering used floral, seaweed, or arabesque marquetry.

Other cabinets were japanned, to imitate lacquer, or were covered in patterned gesso to create a raised and gilded appearance. Now reproduction furniture, Chests on stands were replaced by bureau cabinets, often topped with pediments or domes intended for the display of expensive porcelain. Clothes presses and livery cupboards were commonplace, as were chests of drawers and kneehole desks.

Tables ranged from oak trestles to grand console tables. These were often designed to stand beneath large, ornate mirrors. High-backed chairs with caned seats and backs were popular, as were chairs in the style of Daniel Marot, which had long carved or pierced back splats.

As the century drew to a close, fine furniture, including fitted furniture, was no longer made solely for grand palaces. Simpler, well crafted pieces were also being made for wealthy city merchants and the landed gentry, paving the way for the elegant styles prevalent in the 18th century.

Japanese Lacquer Cabinet On English Stand

Designed to stand against the wall, this cabinet is only decorated on the front. Such fine lacquered pieces would have been great status symbols. The imported Japanese cabinets rests on an English giltwood stand.

Bureau Bookcase

One of a pair, this is a very rare and fine example of a bureau bookcase. Attributed to the partnership of London cabinet makers James Moore and John Gumley, and is decorated with carved and gilded gesso incorporating strapwork with scrolling foliage and floral detail. An arched pediment with a carved shell sits above arched doors with bevelled glass, which open to reveal a fitted interior.

The lower part, with a sloping fall front, encloses a bureau interior. The base contains drawers with drop-ring handles.

France: Henri IV & Louis XIII

The early 17th century was a time of increasing prosperity in France, after a long period of war. Henri IV ruled a country in which styles had changed little since the Renaissance.

Keen to encourage new skills, he established a workshop for craftsmen in the Louvre Palace in 1608. The craftsmen he employed were Italian and Flemish (French craftsmen were sent to serve an apprenticeship in the Low Countries) and, protected by royal patronage, they were allowed to work in Paris without being subject to the punitive membership restrictions of the medieval guild of joiners and furniture makers.

Traditional Forms

The majority of handmade furniture was made of oak or walnut during the reign of Henri IV. The massive double-bodied cupboard with an upper section that was narrower than the lower section, doors with geometric panelling, and bun feet continued to be popular well into the 17th century.

Tables had elaborate heavy bases and chairs were architectural in form, which made then rather stiff and uncomfortable.

Foreign Influences

After Henri IV's death in 1610, his Italian wife Marie de Medici was appointed Regent to the young king. During her reign, there was a building boom in Paris and the nobility and a growing middle class began to furnish their apartments in grand style.

Marie was influential in now antique furniture design. She employed many foreign craftsmen, including Jean Mace, a cabinet maker from the Low Countries, who probably first used veneering in French furniture design, and Italian craftsmen, who introduced boullework and pietra dura inlays. In particular Marie de Medici encouraged the manufacture fitted and non fitted furniture - cabinets inlaid with ebony, which were made in Paris from around 1620 to 1630.

Court Cupboard

English 17th century Oak Court Cupboard, beautiful patina, herringbone inlay, forged hardware. Dated and initialed on upper frieze. C 1620

The early 17th century was a time of increasing prosperity in France, after a long period of war. Henri IV ruled a country in which styles had changed little since the Renaissance.

Keen to encourage new skills, he established a workshop for craftsmen in the Louvre Palace in 1608. The craftsmen he employed were Italian and Flemish (French craftsmen were sent to serve an apprenticeship in the Low Countries) and, protected by royal patronage, they were allowed to work in Paris without being subject to the punitive membership restrictions of the medieval guild of joiners and furniture makers.

Traditional Forms

The majority of handmade furniture was made of oak or walnut during the reign of Henri IV. The massive double-bodied cupboard with an upper section that was narrower than the lower section, doors with geometric panelling, and bun feet continued to be popular well into the 17th century.

Tables had elaborate heavy bases and chairs were architectural in form, which made then rather stiff and uncomfortable.

Foreign Influences

After Henri IV's death in 1610, his Italian wife Marie de Medici was appointed Regent to the young king. During her reign, there was a building boom in Paris and the nobility and a growing middle class began to furnish their apartments in grand style.

Marie was influential in now antique furniture design. She employed many foreign craftsmen, including Jean Mace, a cabinet maker from the Low Countries, who probably first used veneering in French furniture design, and Italian craftsmen, who introduced boullework and pietra dura inlays. In particular Marie de Medici encouraged the manufacture fitted and non fitted furniture - cabinets inlaid with ebony, which were made in Paris from around 1620 to 1630.

Court Cupboard

English 17th century Oak Court Cupboard, beautiful patina, herringbone inlay, forged hardware. Dated and initialed on upper frieze. C 1620

Grand Designs

Furniture during the reign of Louis XIII was monumental and heavy in style. The cabinet, usually on a stand and housing various small drawers, was the most important piece of non fitted furniture of the time. Generally made of walnut or ebony, it would have been decorated with panels, columns, and pilasters.

Ebony veneered cabinets made late into Louis XIII reign are embellished with flat relief carving, carved flowers, and twisted columns. Inspired by Augsburg cabinets that were made in Germany, which used ebony and other exotic materials in a decorative fashion.

The cupboard or buffet was popular at this time, especially in the provinces. This form slowly evolved into an armoire, which was mainly used for storing linens, rather than for the display of expensive household items, such as silver plates or ceramics.

Fall fronts were then added to cabinets, as seen on the typical varguenos, producing an early form of bureau. Small tables intended for the less formal rooms of a house were made in many shapes, but were mostly oblong, with turned legs.

Dining tables now had tops that could be extended, either with hinges or by the use of telescoping leaves. The table bases were usually turned, and H-stretchers provided a popular method of linking the table legs.

Chairs became far more comfortable towards the end of Louis XIII reign, as seats grew lower and wider, and the backs of the chairs became higher. There was a greater emphasis on textiles in Louis XIII handmade furniture, although upholstery was so expensive at this time that only the finest pieces of furniture were covered with textiles. Cushions were used for additional comfort on wooden seats, and chairs made for the upper classes were often covered with fashionable upholstery.

Velvet, damask, leather and needlework were all used. The fabric was fixed into place with rows of small brass tacks, which also served as a decorative element of the chairs. Fringe was added below the back seat rail and along the lower chair rail as an extra embellishment.

Armrests were usually curved and sometimes incorporated an upholstered pad. Chair legs were carved in a sculptural way, similar to the elaborate legs of Brustolon's chairs, or they were turned.

Decorative Detail

The Low Countries, especially Flanders, had a very strong influence on French furniture of the period. Two features typical of Louis XIII furniture were inspired by Flemish furniture - the heavy, moulded panelling in geometric patterns and elaborate turning on legs and stretchers.

Turning was an essential feature of Louis XIII furniture, now antique furniture, both in formal and vernacular pieces. It was now no longer used simply for legs and stretchers, but also to create decorative details on cupboards and cabinets. A piece of furniture would quite often feature more than a single turned design.

Furniture during the reign of Louis XIII was monumental and heavy in style. The cabinet, usually on a stand and housing various small drawers, was the most important piece of non fitted furniture of the time. Generally made of walnut or ebony, it would have been decorated with panels, columns, and pilasters.

Ebony veneered cabinets made late into Louis XIII reign are embellished with flat relief carving, carved flowers, and twisted columns. Inspired by Augsburg cabinets that were made in Germany, which used ebony and other exotic materials in a decorative fashion.

The cupboard or buffet was popular at this time, especially in the provinces. This form slowly evolved into an armoire, which was mainly used for storing linens, rather than for the display of expensive household items, such as silver plates or ceramics.

Fall fronts were then added to cabinets, as seen on the typical varguenos, producing an early form of bureau. Small tables intended for the less formal rooms of a house were made in many shapes, but were mostly oblong, with turned legs.